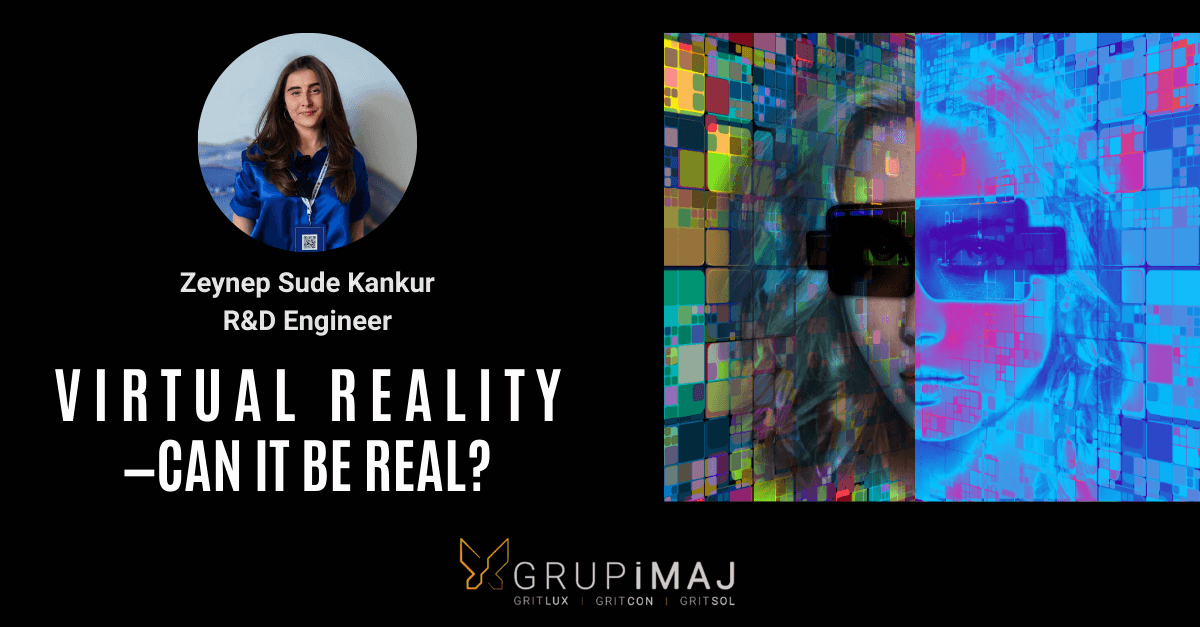

Can Virtual Reality Be Real?

Since antiquity, thinkers have tried to explain “the real” by abstracting it away from human beings and consciousness, defining it as the totality of what is concrete and objective, independent of the human mind. But what happens if an advancing technology flips your sense of reality upside down? How do you begin to tell the real from the virtual?

It sounds like a question pulled straight out of a dystopia, doesn’t it? Yet it isn’t. With the technologies of the 21st century, we can virtualize what already exists—and we can build entirely new, artificial realities. Sometimes these constructed worlds are so convincing that they make us pause and ask, “Is this real?” If two things can be so different and still feel so similar, how will we distinguish them? And more importantly: what is this thing we call “real” in the first place? Let’s start there.

So, What Is “Real”?

The search for reality is one of philosophy’s most fundamental problems. From Plato to Descartes, many philosophers questioned what, within a changing and transforming world, can truly be called real—and often they arrived at a vast uncertainty.

Still, within that uncertainty, many thinkers made room for perception itself. In other words, reality can also be defined in relation to how we perceive it. Put simply: the world is as real as I can perceive it.

The reality we grasp through our senses may open the door to truth—but truth and reality are intertwined yet not identical concepts. If the first step of the bridge between them begins with our senses and our perception, then this is exactly where virtual reality and related technologies enter our lives: they open the door to a new world and reshape humanity’s search for truth.

Looking at Life Through a New Pair of Glasses

With AR, XR, MR, and VR technologies, we can reconstruct reality in digital environments—or manipulate it by blending the physical world with the virtual one.

Let’s focus on VR. It can be used in education, healthcare, manufacturing, entertainment, and industrial design. It draws particular attention in the entertainment industry. In VR, entirely different worlds can be designed, and through stimuli directed at your senses, you can be made to feel like part of that virtual universe. But in the end, your body remains outside.

Of course, the technology we have today may not fully help you imagine where this is heading. For those who haven’t watched it, I’d recommend the series 3 Body Problem. If you recall, the story features a kind of headset technology used by aliens to convey their world to humans—and it was so advanced that you could even feel injuries you sustained inside the simulation as you exited it.

A little unsettling, isn’t it? After all, if we perceive an “artificial” reality through our senses, can we still call it artificial? If our bodies and senses are fully included in the process, do we have to accept virtual reality as simply another variation of what we already call reality—and eventually build systems that resemble the one we’re living in now?

Questioning Keeps Us Close to Reality

But I actually want to shift your perspective with a different question:

How much do we question the reality of the world we live in—or the “truths” of the system we’re trying to exist within, and the elements that make up that system?

In everyday life, as we lose ourselves in the flow of things, we rarely stop to question the nature of what surrounds us. Instead of interrogating whether events, news, or claims are real, we often respond automatically—behaviorally, reactively, and in line with whatever stimuli we’re fed.

But if we lifted our heads for a moment—from the road we’re walking, the series we’re watching, the news we’re consuming, the newspaper we’re skimming—and simply asked, “Is this real?” then the search for truth would begin.

So it isn’t only our perceptual abilities that matter. Assigning our minds the responsibility to question—giving skepticism a mission—might be what enables us to distinguish actual reality, artificial reality, and even constructed reality.

When we realize that reality is far more than what is presented to us, we begin to seek it—and even to desire it. We can debate at length what the “reality” of the virtual world is and what kind of system it requires. But how do we know that the world we inhabit is not itself a simulation? How do we know that so many things labeled “real” haven’t simply been placed into the display windows of media—or turned into social media trends?

Maybe just pause for a second… and lift your head from the phone.

Get in Touch

For inquiries about our products, technical support, or partnership opportunities, please click the button below to access our contact form. Let’s illuminate your projects together!

Get in Touch

For inquiries about our products, technical support, or partnership opportunities, please click the button below to access our contact form. Let’s illuminate your projects together!